Disclosure: No authors have a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this production or publication.

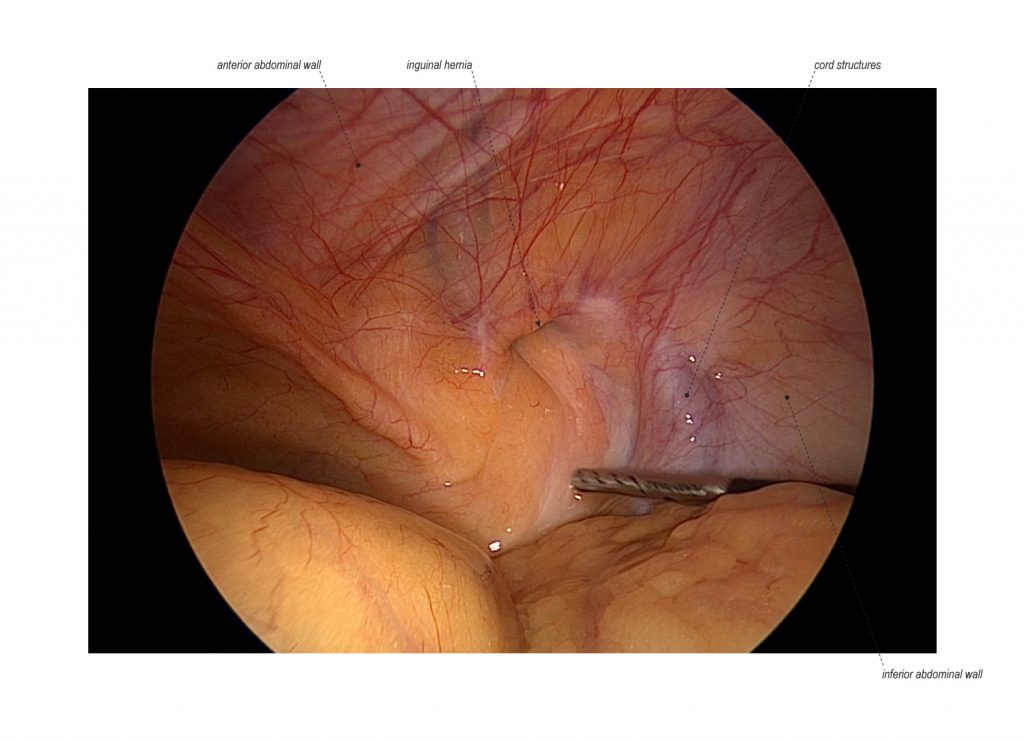

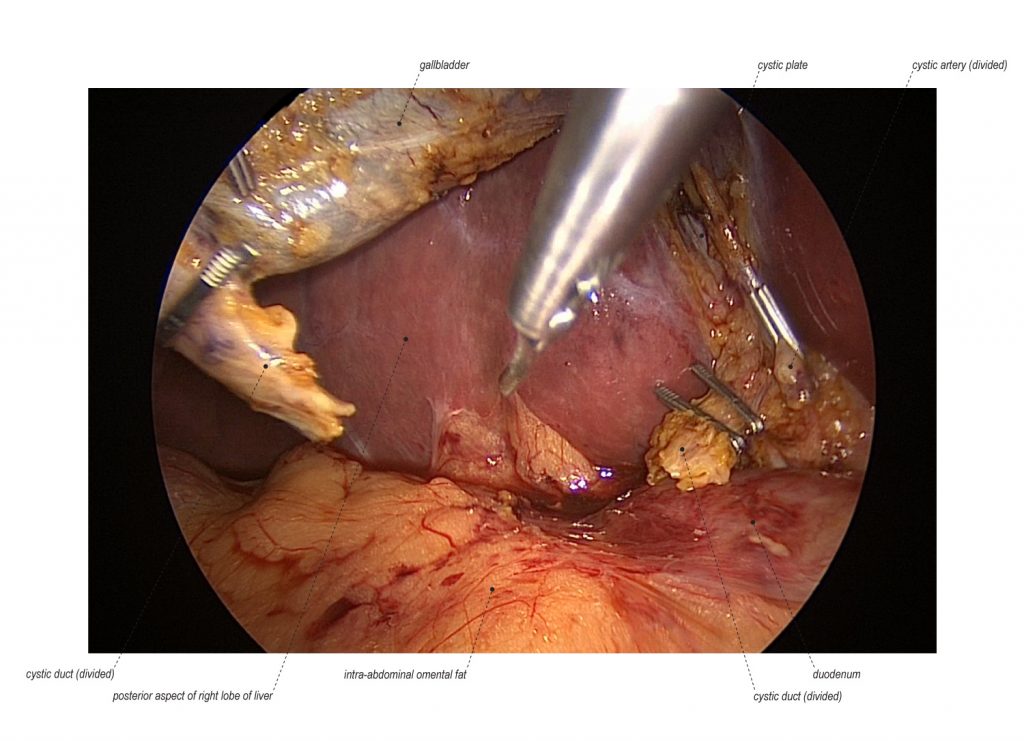

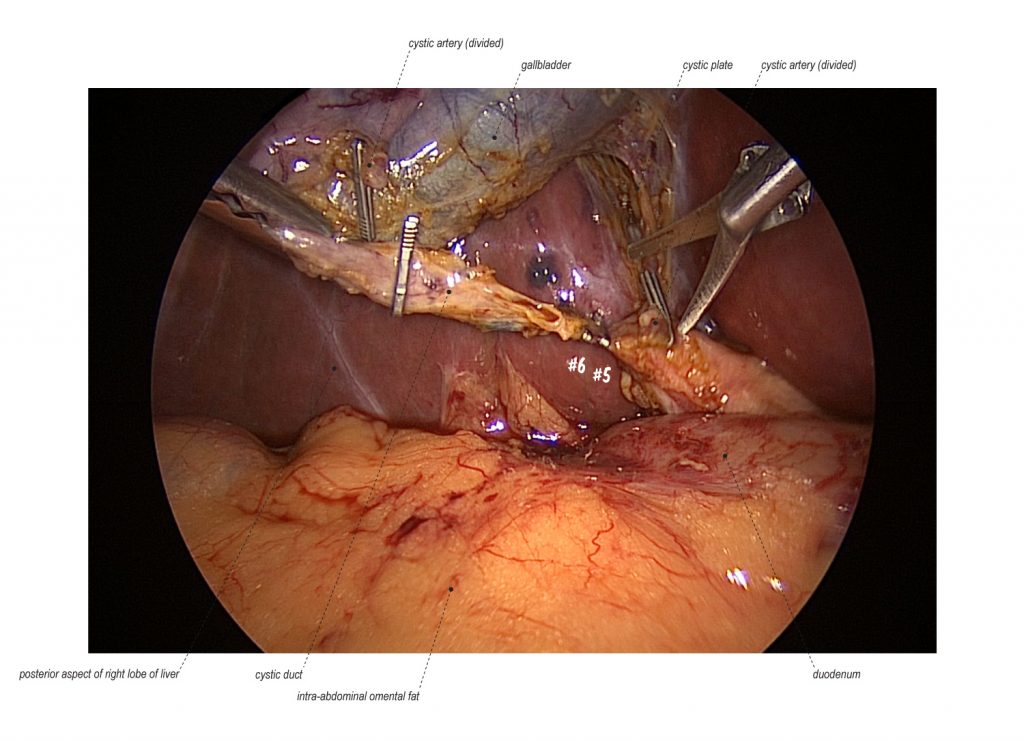

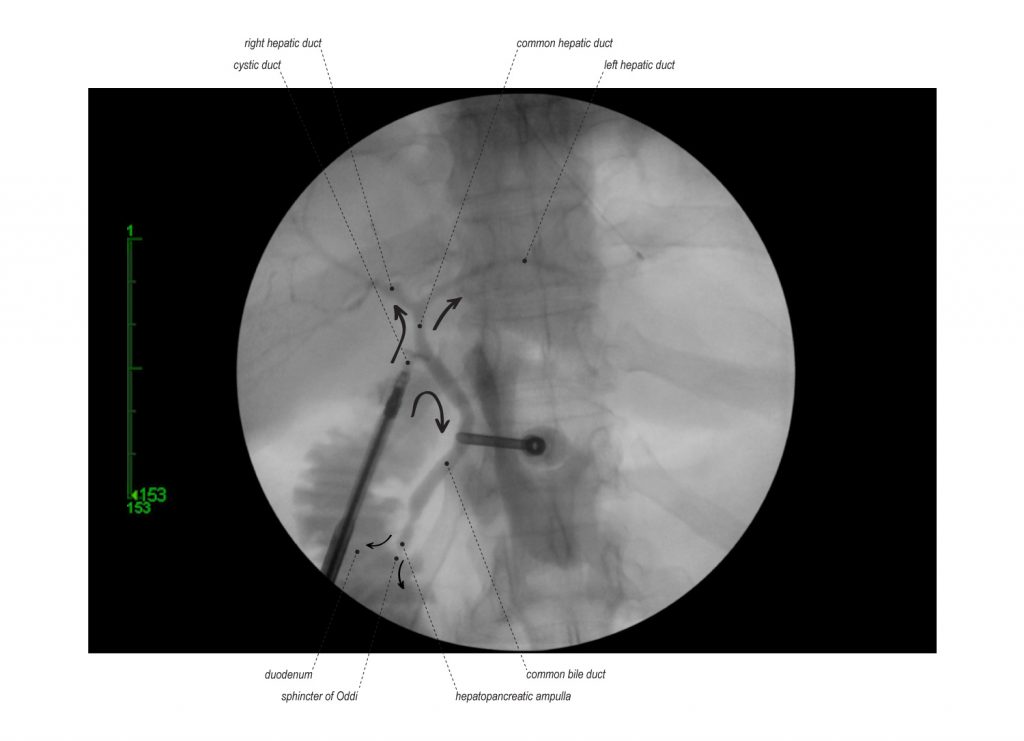

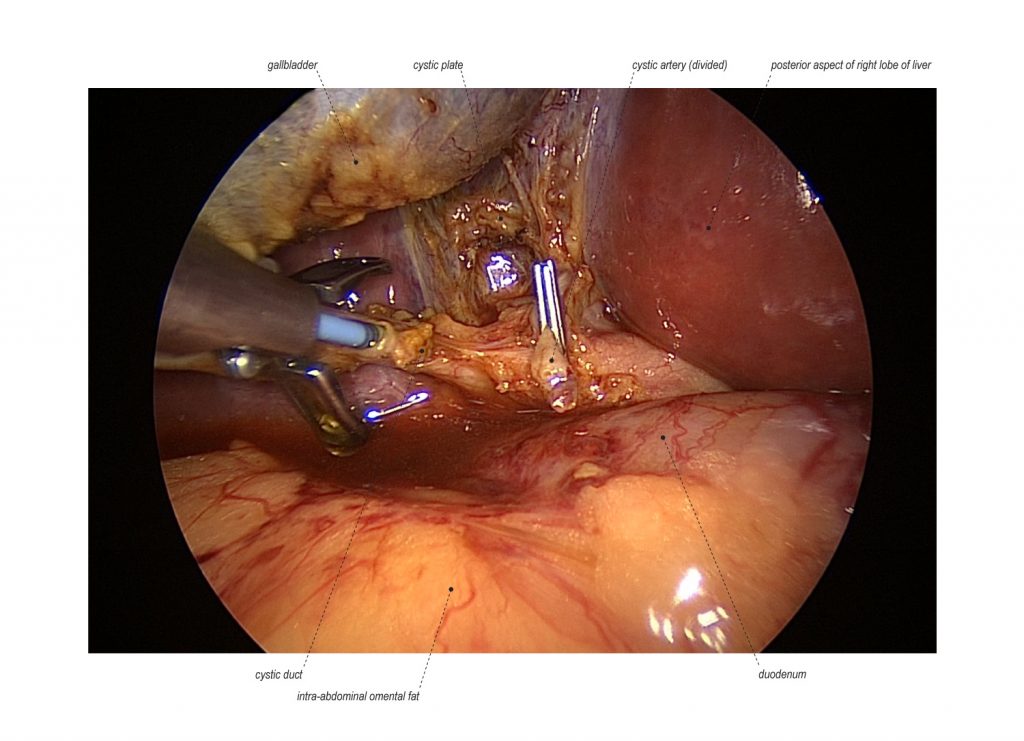

Minimal invasive laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the typical surgical treatment for cholelithiasis (gallstones), where patients present with a history of upper abdominal pain and episodes of biliary colic. The classic technique for minimal invasive laparoscopic cholecystectomy involves four ports: one umbilical port, two subcostal ports, and a single epigastric port. The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) has instituted a six-step strategy to foster a universal culture of safety for cholecystectomy and minimize risk of bile duct injury. The technical steps are documented within the context of the surgical video for (1) achieving a critical view of safety for identification of the cystic duct and artery, (2) intraoperative time-out prior to management of the ductal structures, (3) recognizing the zone of significant risk of injury, and (4) routine intraoperative cholangiography for imaging of the biliary tree. In this case, the patient presented with symptomatic biliary colic due to a gallstone seen on the ultrasound in the gallbladder. The patient was managed with mini-laparoscopic cholecystectomy using 3mm ports for the epigastric and subcostal port sites with intraoperative fluoroscopic cholangiogram. Specifically, the senior author encountered a tight cystic duct preventing the insertion of the cholangiocatheter and the surgical video describes how the author managed the cystic duct for achieving a cholangiogram, in addition to the entire technical details of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Standard:

Extended:

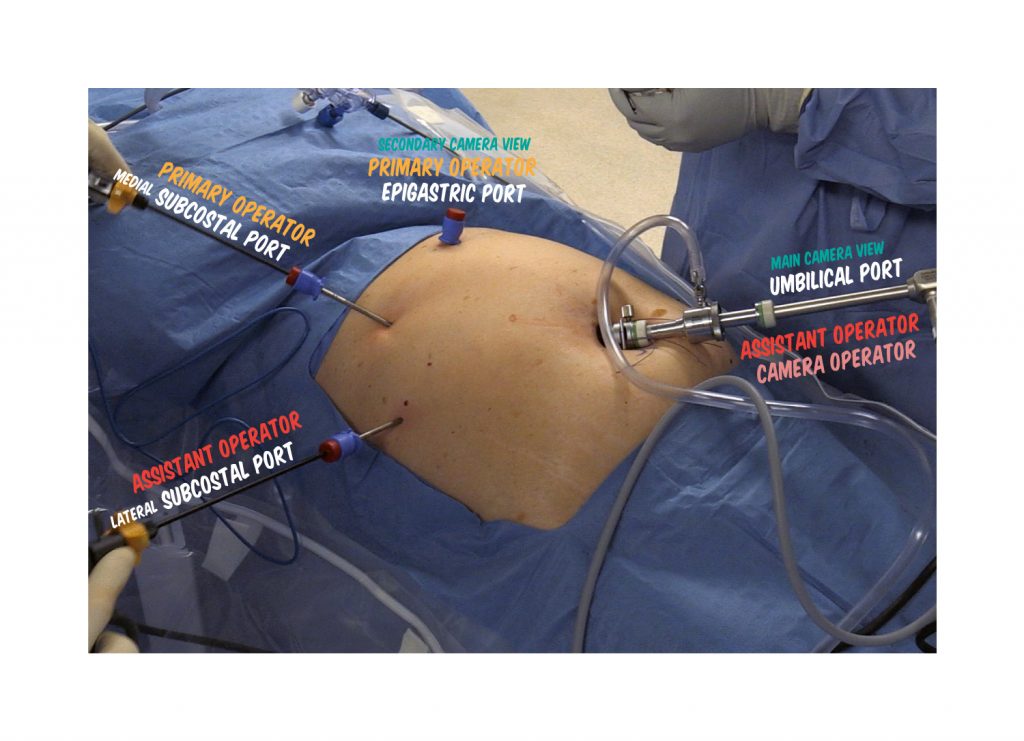

POSITION

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table. The primary operating surgeon stands on the patient’s left and operates using the medial subcostal and epigastric ports. The surgical assistant stands on the patient’s right and operates using the lateral subcostal port and directs laparoscopic camera view through the umbilical port or with a third assistant as the camera operator. At training institutions, the senior surgeon can direct the procedure and provide retraction through the lateral and medial subcostal ports. Laparoscopic monitors are placed, on the patient’s left and right, at eye level directly across the surgical field from the surgeon and assistant.

INCISIONS FOR ABDOMINAL ACCESS

Umbilical Port

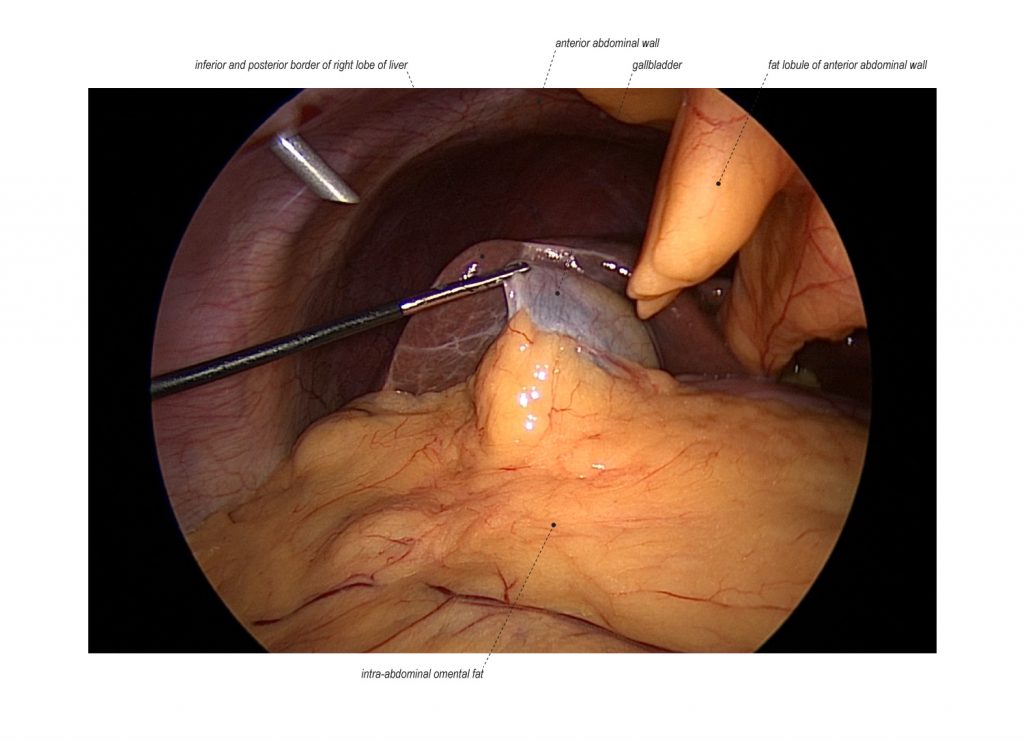

The first incision is made at the umbilicus with the initial entry into the abdominal cavity using an open (Hasson) technique. The laparoscope is introduced through the umbilical trocar for initial abdominal inspection. The umbilical port is also used for introduction of clip applicator.

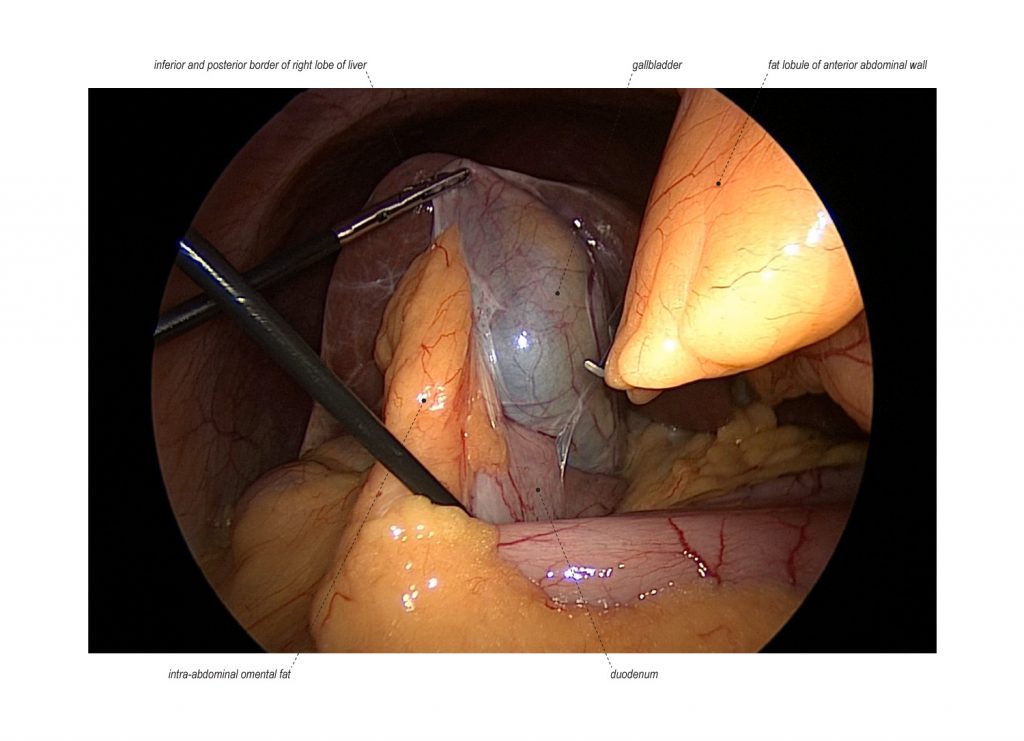

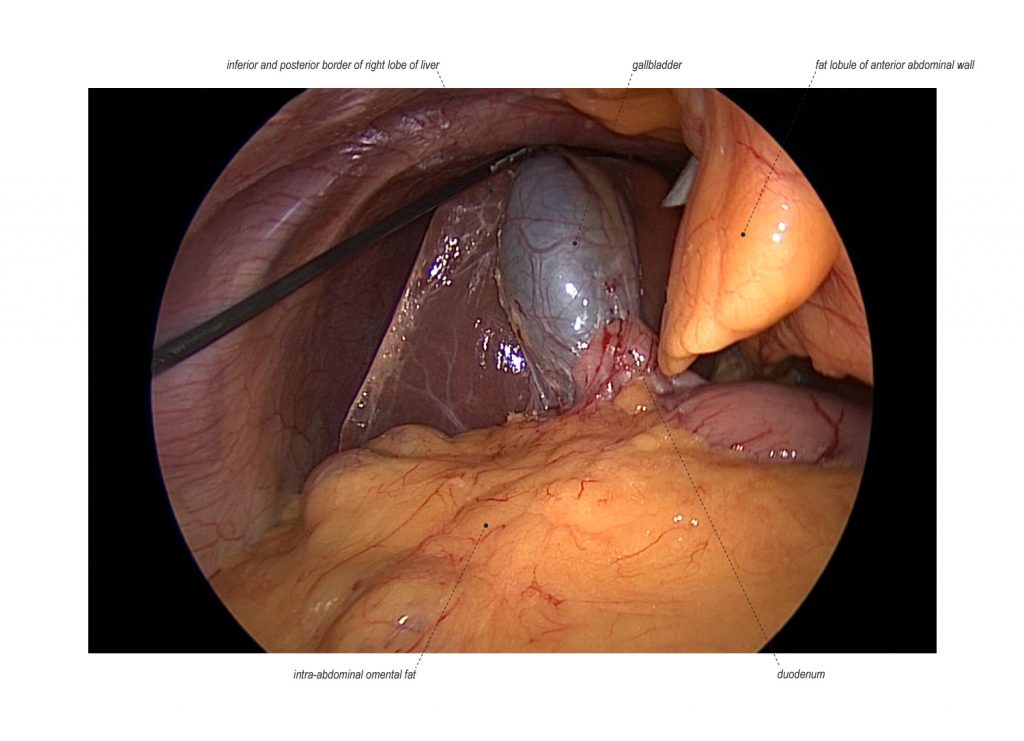

Lateral Subcostal Port

The second incision is made to introduce a 3mm trocar to serve as the lateral subcostal port. This incision is placed 1-2 cm inferior to the right subcostal margin, at the mid-axillary line halfway between the subcostal margin and anterior superior iliac spine. This port utilizes grasping forceps to grasp the fundus of the gallbladder for manipulation with the liver superiorly to expose the posterior aspect of the gallbladder and its trunk. This port is performed under direct vision.

Medial Subcostal Port

The third incision is made to introduce a 3mm trocar to serve as the medial subcostal port. This incision is placed 1-2 cm inferior to the right subcostal margin, at the right midclavicular line just below the inferior border of the liver. This port utilizes grasping forceps to provide counter-traction by the primary surgeon, scissors, and introduction of the cholangiocatheter for intraoperative fluoroscopic cholangiogram. In this case, this port was upsized to a 5mm trocar to handle large sharp dissecting scissors to manage a tight cystic duct.

Epigastric Port

The fourth incision is made to introduce a 3mm trocar to serve as the epigastric port. This incision is placed 1-2 cm inferior to the mid-subcostal margin, in the high epigastric/subxiphoid region, just left to the falicform ligament. Instrumentation includes L-Hook Bovie, dissecting scissors, Maryland forceps, and secondary camera placement for clipping and gallbladder extraction.

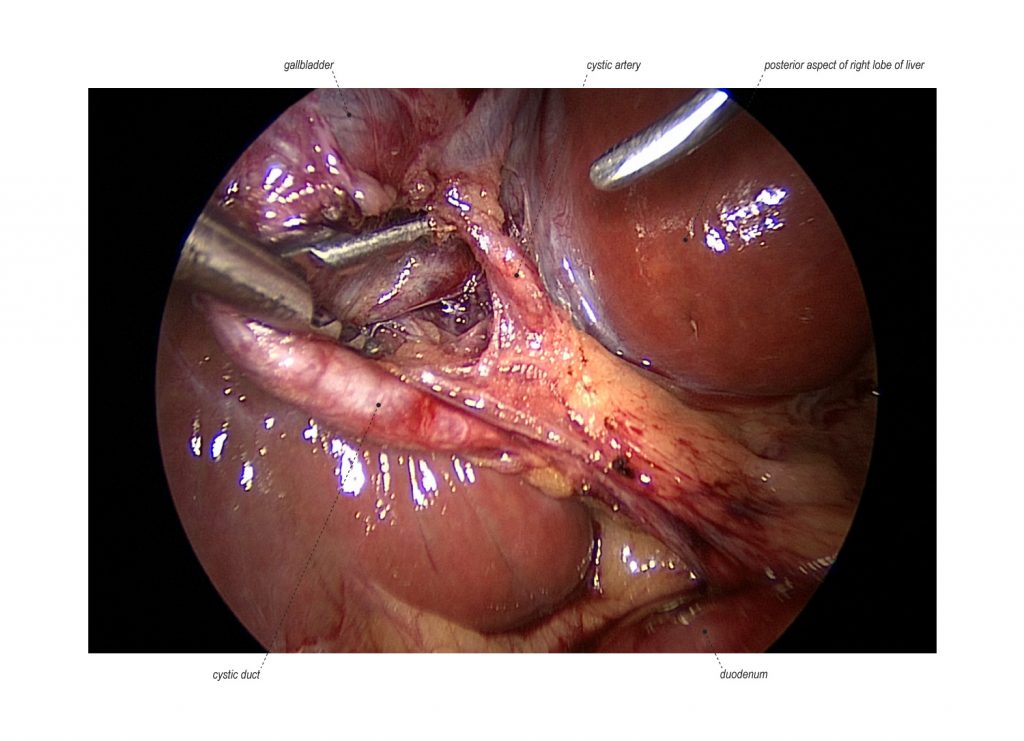

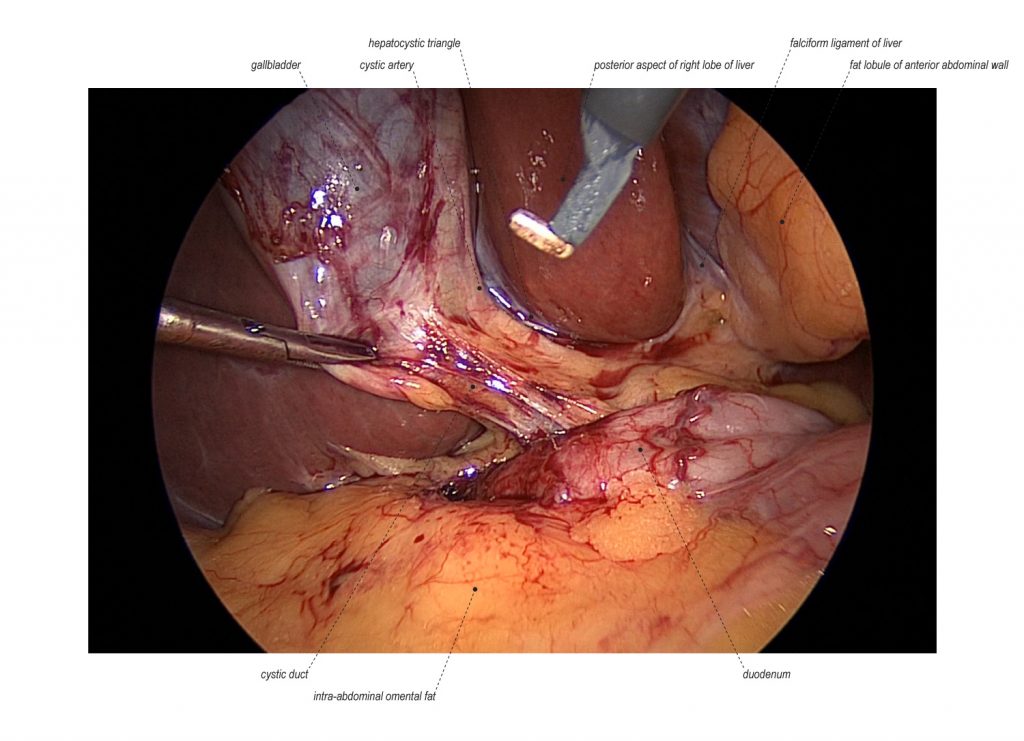

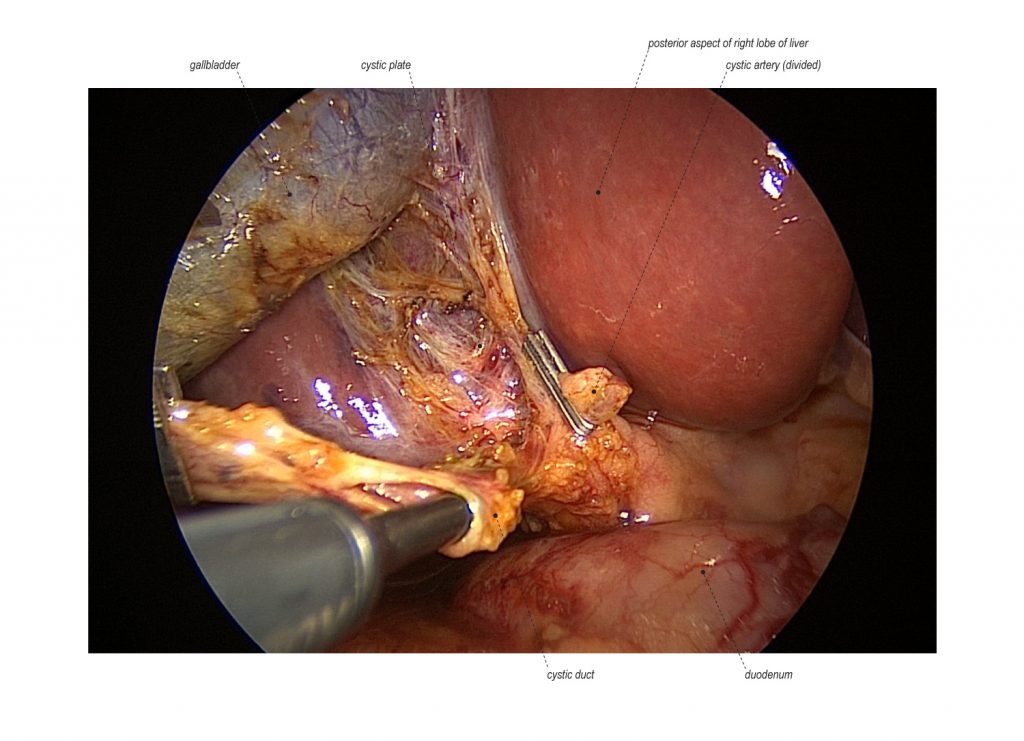

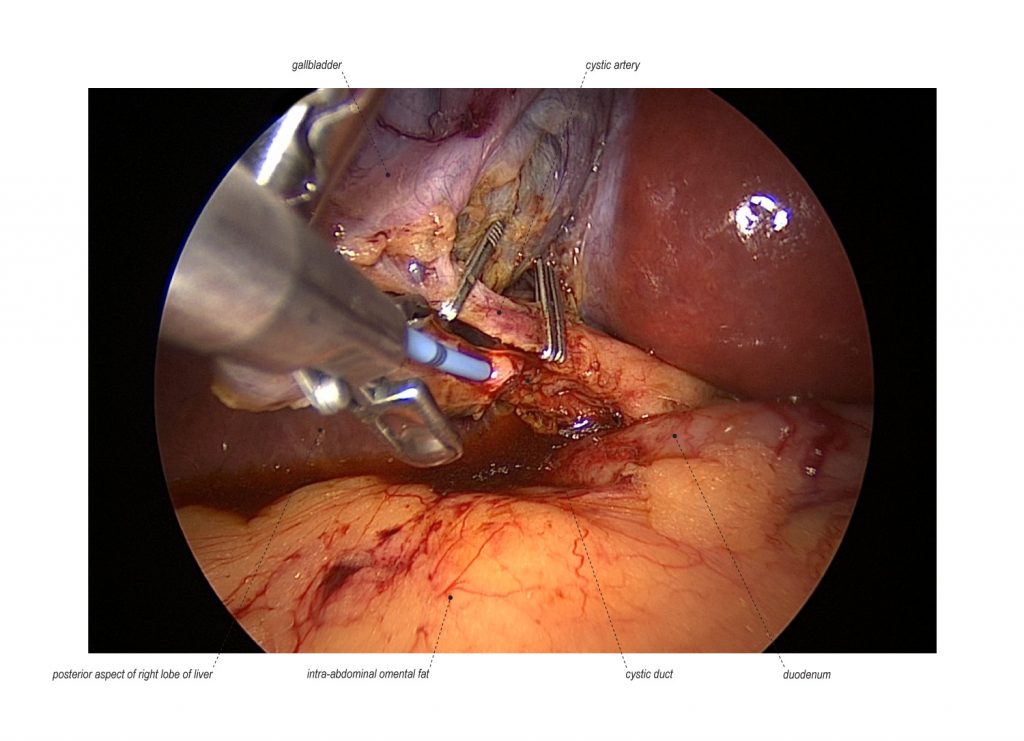

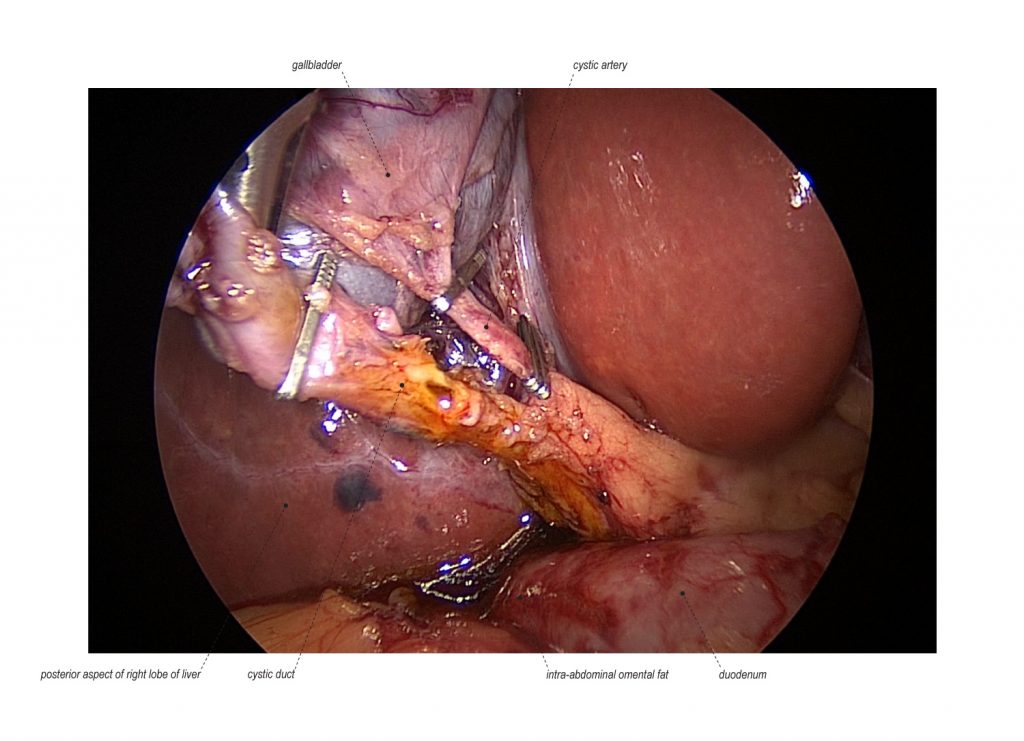

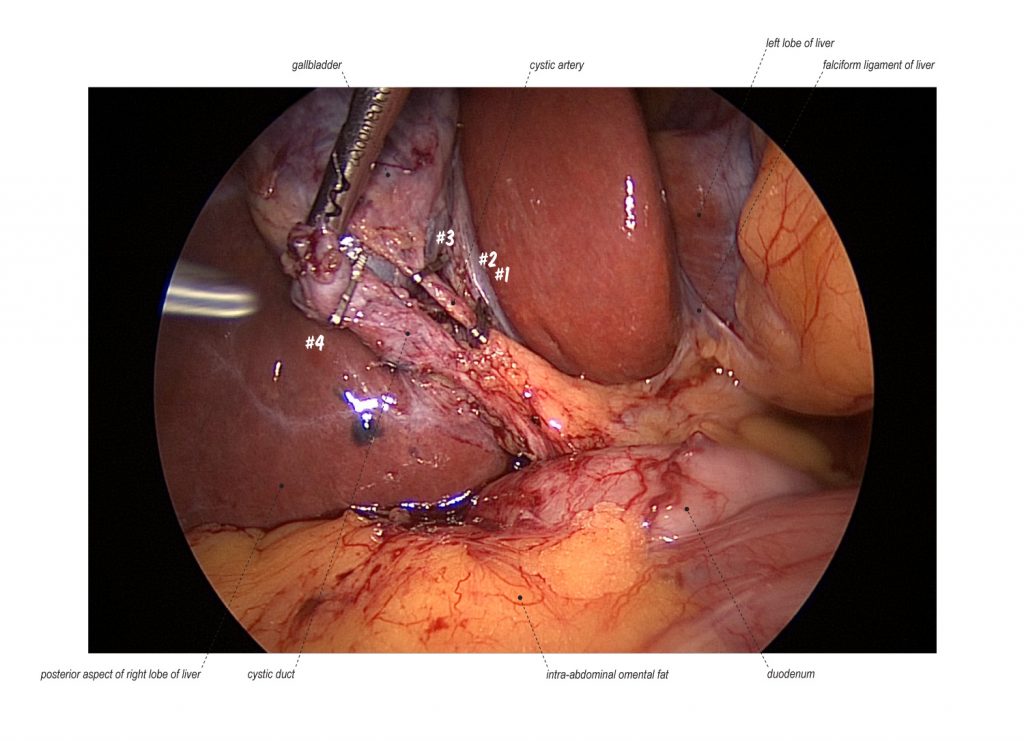

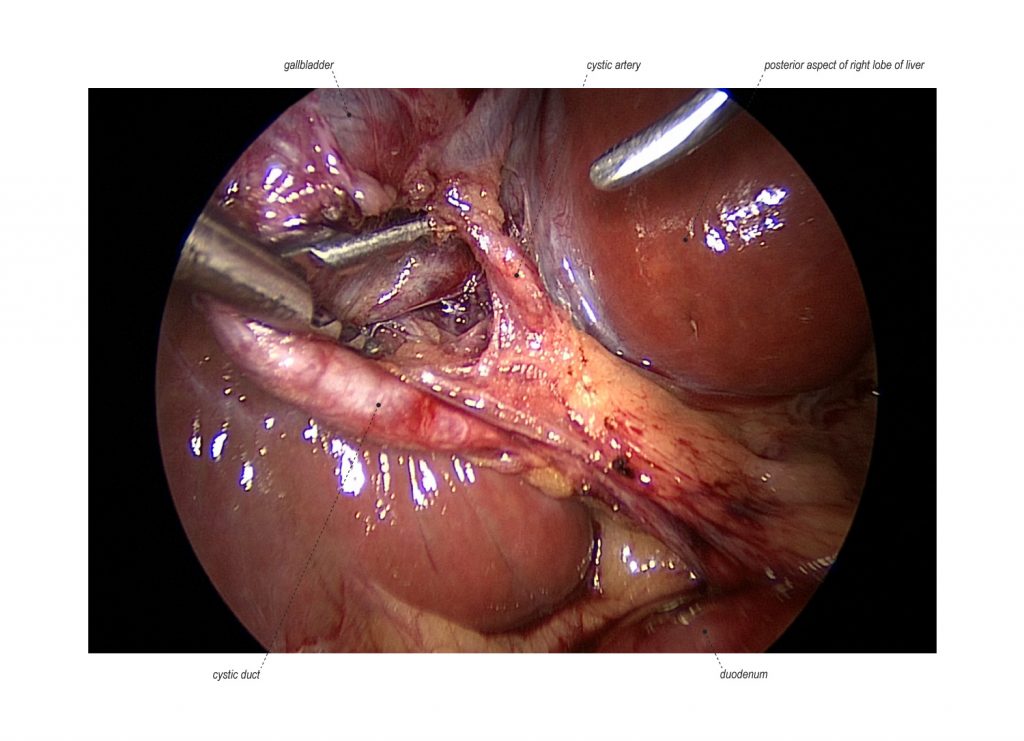

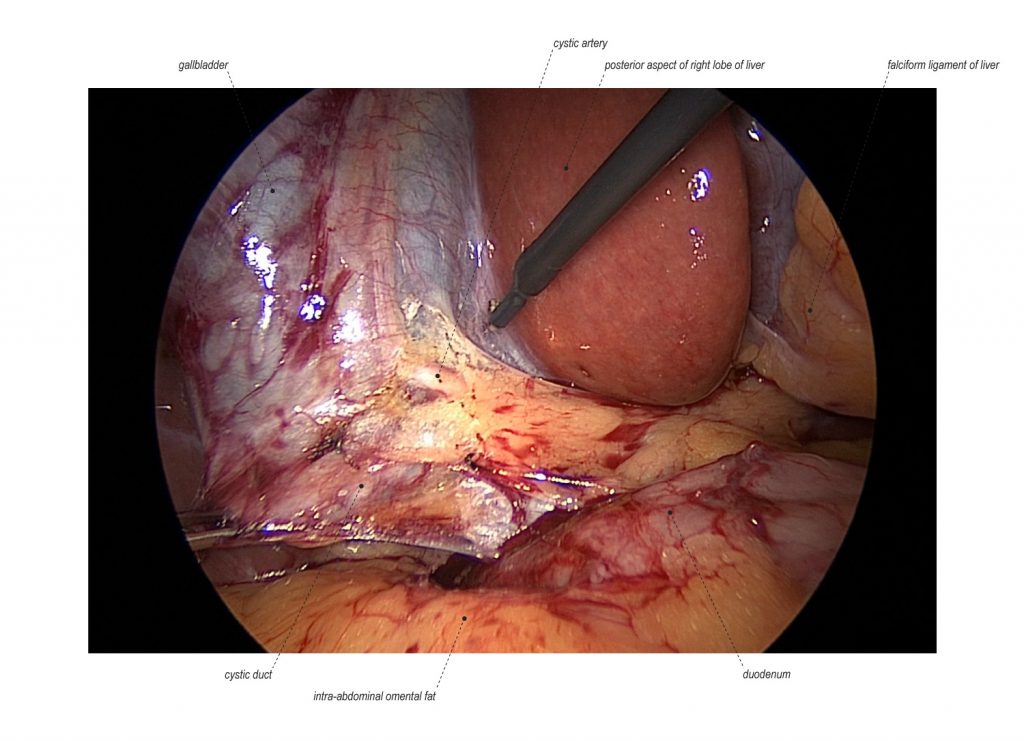

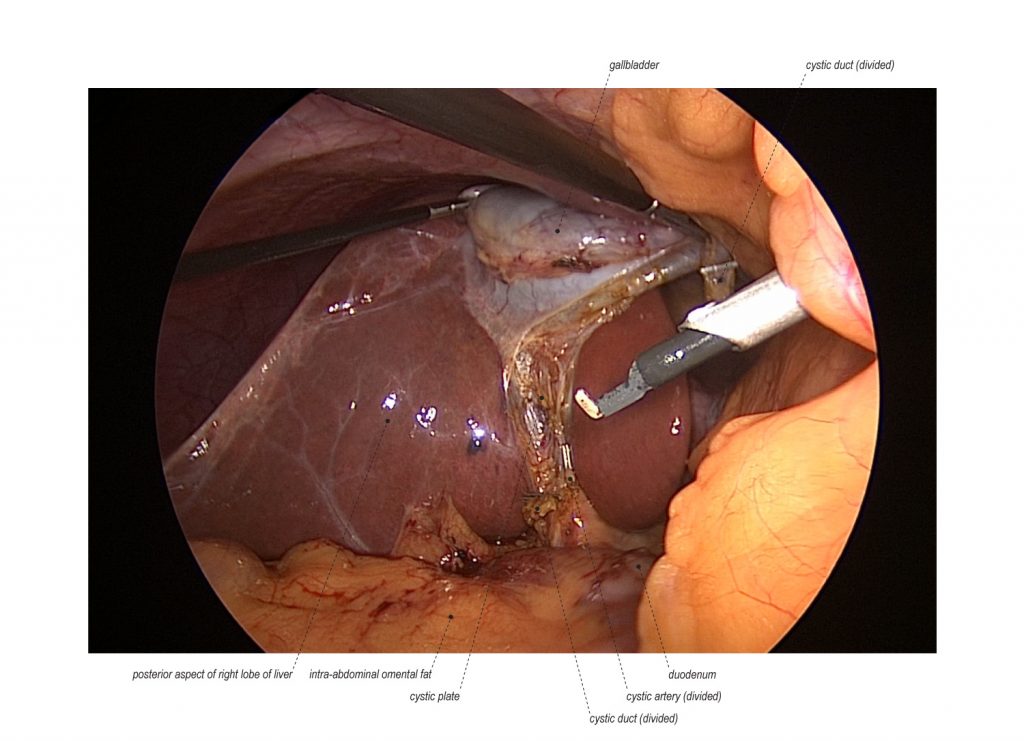

SPECIFIC CASE SURGICAL JUDGEMENT

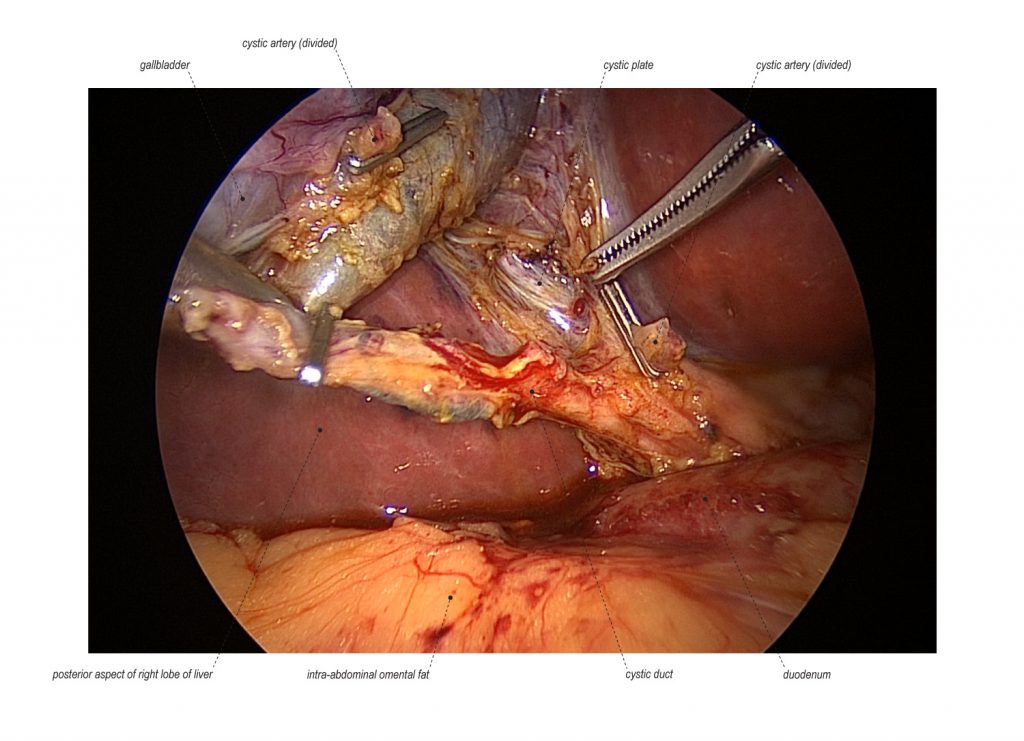

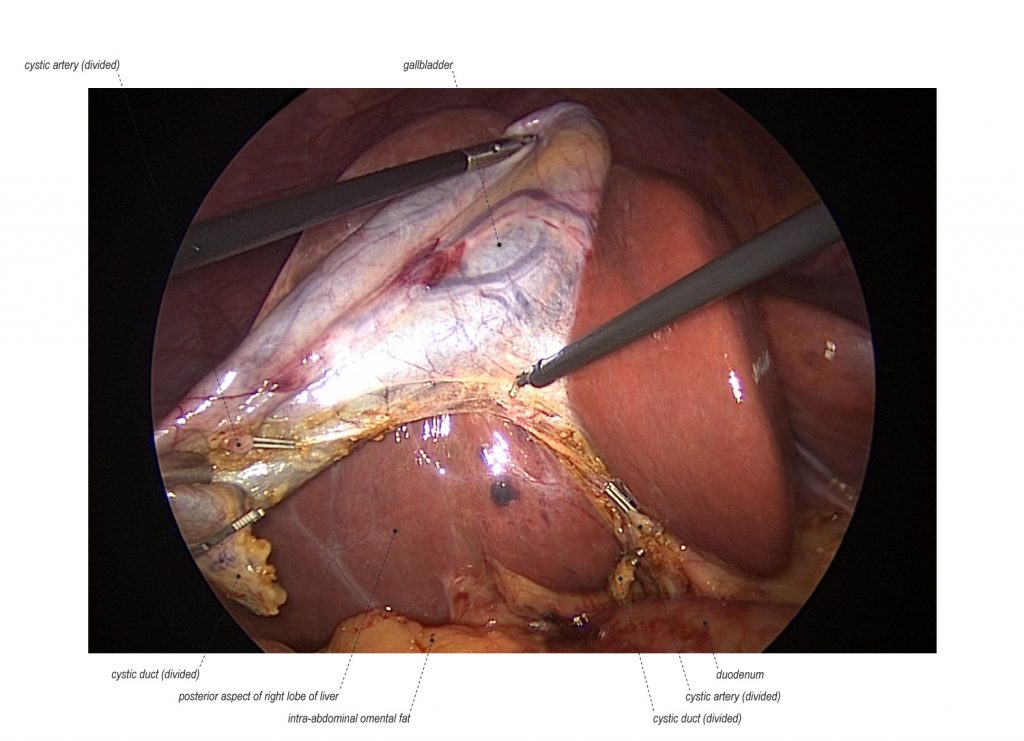

In this case, there was difficulty during the insertion of the cholangiocather into the cystic duct for the intraoperative cholangiogram. This was due to a tight cystic duct that involved careful dissection and cholangiogram of the cystic duct. This required an upsizing of medial subcostal port to accommodate larger instrumentation for careful cholangiography within the duct, division of cystic artery, and further clearance of the fat and fibrous tissue from the cystic duct. In this order, the cystic duct was proximally mobilized to allow for the opening of the cystic duct and successful insertion of the cholangiocather. This surgical video demonstrates the careful handling of the cystic duct for this operative finding of a restrictive and a tight cystic duct.

SIX-STEP STRATEGY FOR SAFETY IN CHOLECYSTECTOMY (LINK)

The six-step strategy for creating a universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy was established by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). This strategy was developed to minimize bile duct injuries due to the increased injury rates since the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, occurring in about 3 per 1,000 procedures of over 750,000 cholecystectomies performed per year (1-3). Bile duct injuries can be life-altering complication which leads to significant morbidity and costs. (4,5). Due to the infrequences of bile duct injuries, definitive studies comparing methods to minimize these complications will likely never be performed. Thus, SAGES recommend the following strategy for minimizing risk of bile duct injury.

- Critical View of Safety (CVS) method of identification of cystic duct and artery.

- Intraoperative time-out prior to clipping, cutting, or transecting any ductal structures.

- Awareness of aberrant ductal and arterial anatomy.

- Use of intraoperative cholangiography or other imaging methods.

- Recognition of approach to zone of significant risk and alteration of surgical approach depending on CVS findings.

- Help from another surgeon when dissection or conditions are difficult.

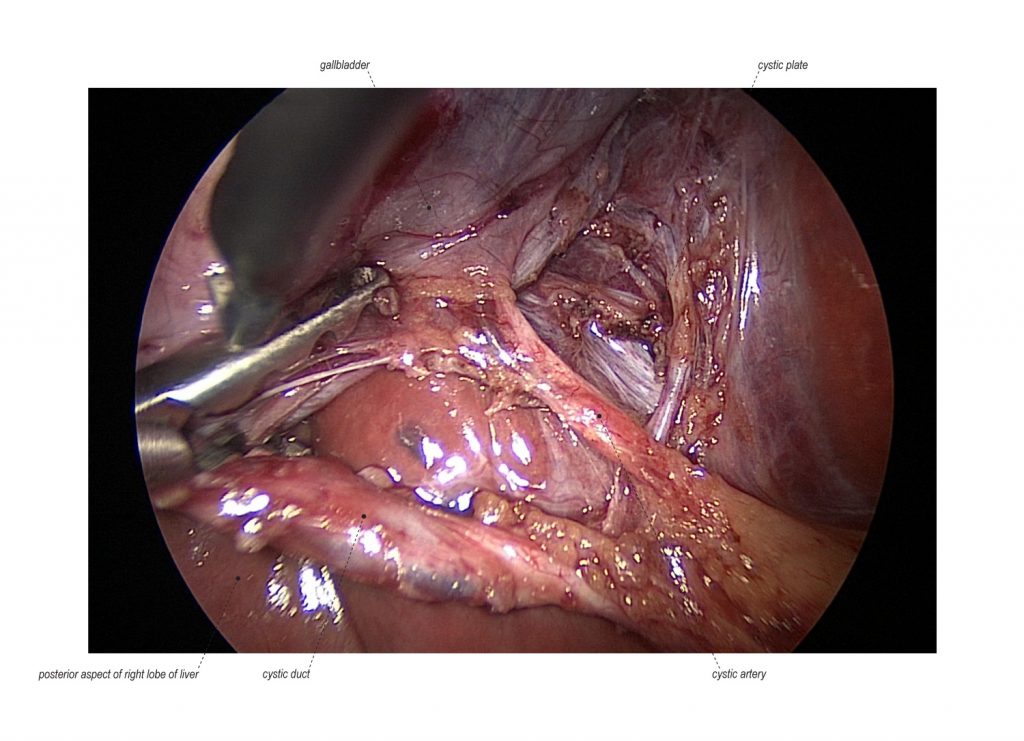

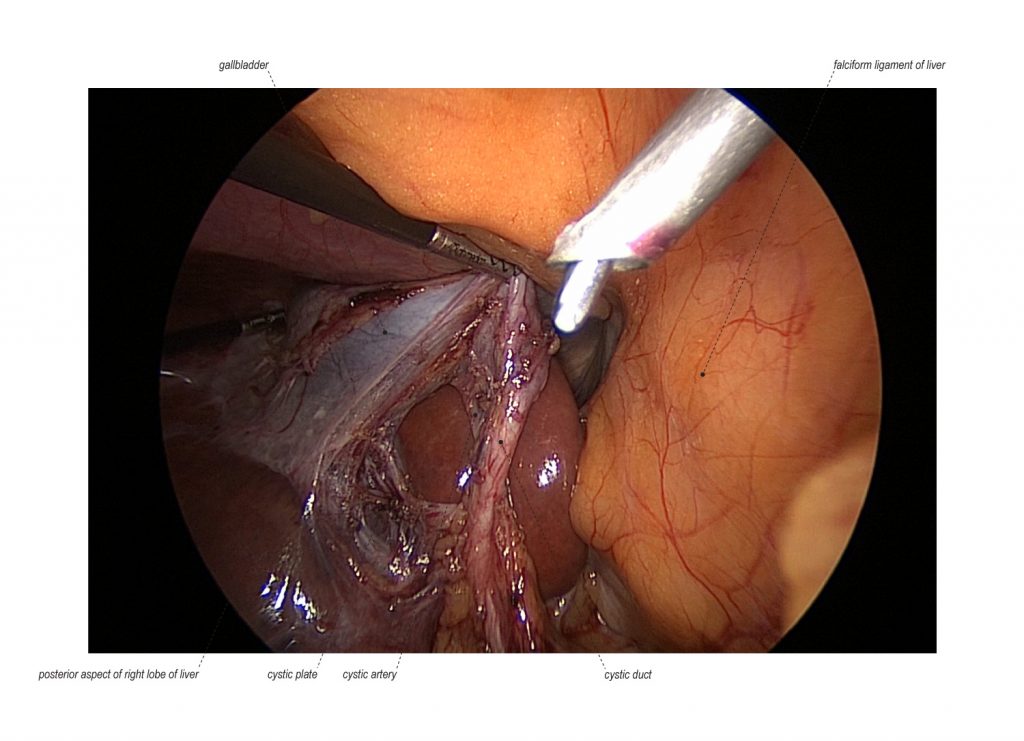

CRITICAL VIEW OF SAFETY METHOD OF IDENTIFICATION IN CHOLECYSTECTOMY

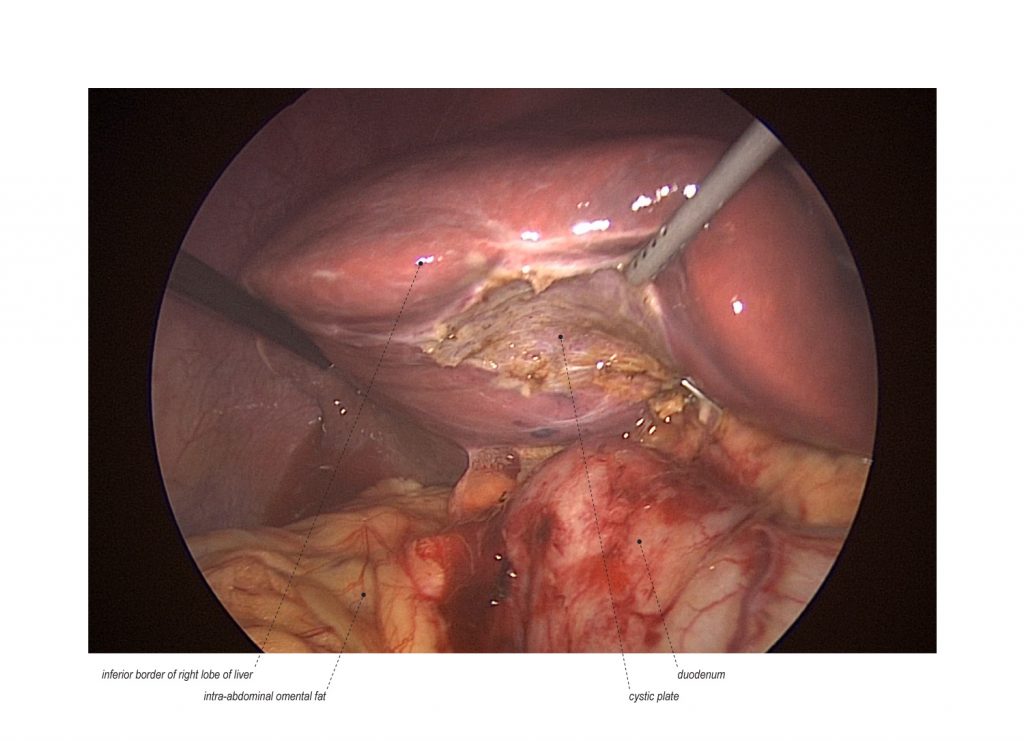

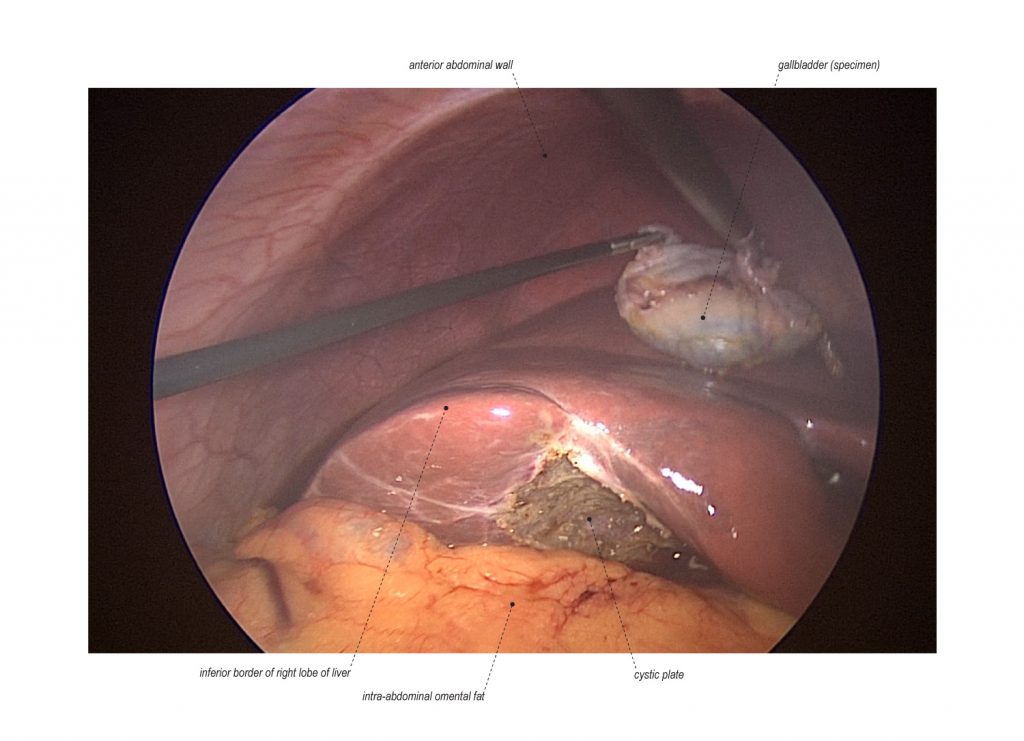

The term “critical view of safety” CVS was introduced by an analytical review in response to the increase rate of biliary injury associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (6). CVS is a method for the safe identification of the cystic duct and artery, after which the lower one-third of the gallbladder has been mobilized from the cystic plate (7). This mobilization of the gallbladder allows for the clear identification of these two structures for assessment of aberrant anatomy, however more importantly for the safe clipping, cutting, and transection of the cystic duct and artery. The CVS method has been assessed as part of a compressive six-step strategy for safety in cholecystectomy for reducing biliary injuries (8).

- Clearing the hepatocystic triangle of fat and fibrous tissue.

- Mobilization of the lower one-third of the gallbladder from the cystic plate.

- Identification of two anatomical structures: cystic duct and cystic artery.

POST-OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

For uncomplicated and elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, patients can drink clear liquids once awake after anesthesia with their diet being advanced as tolerated. In most healthy and reliable patients with good home support, they can leave the hospital within six hours after surgery. The patients have no activity restrictions unless the umbilical incision was particularly large, therefore limited heavy lifting is recommended for the first few weeks. Most patients return to work within one week and follow-up occurs 2-4 weeks after surgery.

REFERENCES

- Hurley V, Brownlee S. Cholecystectomy in California: A Close-Up of Geographic Variation. California Healthcare Foundation 2011.

- MacFadyen BV, Jr., Vecchio R, Ricardo AE, Mathis CR. Bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The United States experience. Surgical Endoscopy 1998; 12:315-21. PMID: 9543520.

- Buddingh KT1, Weersma RK, Savenije RA, van Dam GM, Nieuwenhuijs VB. Lower rate of major bile duct injury and increased intraoperative management of common bile ductstones after implementation of routine intraoperative cholangiography. J Am Coll Surg. 2011 Aug;213(2):267-74. PMID: 21459631.

- Kern KA. Malpractice litigation involving laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cost, cause, and consequences. Archives of Surgery 1997; 132:392-7; discussion 7-8. PMID: 9108760.

- Flum DR, Flowers C, Veenstra DL. A cost-effectiveness analysis of intraoperative cholangiography in the prevention of bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2003; 196:385-93. PMID: 12658690.

- Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 180:101-125. PMID: 8000648.

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2010; 211:132–138. PMID: 20610259.

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. The Critical View of Safety: Why It Is Not the Only Method of Ductal Identification Within the Standard of Care in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2017 Mar;265(3):464-465. PMID: 27763898.

REFERENCES (SENIOR AUTHOR)

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. The Critical View of Safety: Why It Is Not the Only Method of Ductal Identification Within the Standard of Care in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2017 Mar;265(3):464-465. PMID: 27763898.

- Pucci MJ, Brunt LM, Deziel DJ. Safety First, Total Cholecystectomy Second. J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Sep;223(3):543-4. PMID: 27569667.

- Strasberg SM, Pucci MJ, Brunt LM, Deziel DJ. Subtotal Cholecystectomy-“Fenestrating” vs “Reconstituting” Subtypes and the Prevention of Bile Duct Injury: Definition of the Optimal Procedure in Difficult Operative Conditions. J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Jan;222(1):89-96. PMID: 26521077.

- Brauer DG, Hawkins WG, Strasberg SM, Brunt LM, Jaques DP, Mercurio NR, Hall BL, Fields RC. SAGES expert Delphi consensus: critical factors for safe surgical practice in laparoscopiccholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2015 Nov;29(11):3074-85. PMID: 25669635.

- McKinley SK, Brunt LM, Schwaitzberg SD. Prevention of bile duct injury: the case for incorporating educational theories of expertise. Surg Endosc. 2014 Dec;28(12):3385-91. PMID: 24939158.

- Brunt LM. Commentary on “Incisional hernia rate may increase after single-port cholecystectomy”. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012 Oct;22(8):738-9. PMID: 23039700.

- Brunt LM. Commentary on “Cystic duct leaks after laparoendoscopic single-site cholecystectomy”: a word of caution. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012 Jul-Aug;22(6):538. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.9993. PMID: 22812574.

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010 Jul;211(1):132-8. PMID: 20610259.

- Rawlings A, Hodgett SE, Matthews BD, Strasberg SM, Quasebarth M, Brunt LM. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial experience with critical view of safety dissection and routine intraoperative cholangiography. J Am Coll Surg. 2010 Jul;211(1):1-7. PMID: 20610242.

- Jenkins ED, Yom V, Melman L, Brunt LM, Eagon JC, Frisella MM, Matthews BD. Prospective evaluation of adhesion characteristics to intraperitoneal mesh and adhesiolysis-related complications during laparoscopic re-exploration after prior ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2010 Dec;24(12):3002-7. PMID: 20445995.

- Pierce RA, Jonnalagadda S, Spitler JA, Tessier DJ, Liaw JM, Lall SC, Melman LM, Frisella MM, Todt LM, Brunt LM, Halpin VJ, Eagon JC, Edmundowicz SA, Matthews BD. Incidence of residual choledocholithiasis detected by intraoperative cholangiography at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients having undergone preoperative ERCP. Surg Endosc. 2008 Nov;22(11):2365-72. PMID: 18322745.

- Brunt LM, Quasebarth MA, Dunnegan DL, Soper NJ. Outcomes analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the extremely elderly. Surg Endosc. 2001 Jul;15(7):700-5. PMID: 11591971.

- Jones DB, Soper NJ, Brewer JD, Quasebarth MA, Swanson PE, Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Chronic acalculous cholecystitis: laparoscopic treatment. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1996 Apr;6(2):114-22. PMID: 8680633.

- Soper NJ, Brunt LM. The case for routine operative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1994 Aug;74(4):953-9. Review. PMID: 8047951.

- Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Kerbl K. Laparoscopic general surgery. N Engl J Med. 1994 Feb 10;330(6):409-19. Review. PMID: 8284008.

- Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Callery MP, Edmundowicz SA, Aliperti G. Role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of acute gallstone pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1994 Jan;167(1):42-50; discussion 50-1. PMID: 8311139.

- Soper NJ, Flye MW, Brunt LM, Stockmann PT, Sicard GA, Picus D, Edmundowicz SA, Aliperti G. Diagnosis and management of biliary complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1993 Jun;165(6):663-9. PMID: 8506964.

- Farn J, Hammerman AM, Brunt LM. Intraoperative pneumothorax during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a complication of prior transdiaphragmatic surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993 Jun;3(3):219-22. PMID: 8111562.